I hate making word and grammar mistakes. I can still vividly remember when I was 17 visiting my sister at the University of Chicago where she was a graduate student and playing Trivial Pursuit with her friends. They were REALLY smart, needless to say, and I read aloud a card mispronouncing the word “municipal.” I thought it was munincipal, with a second “n,” so that’s how I said it, and, I mean, I can still hear the laughter and all of them correcting me. Her friends, not my sister.

Even today when I send off an email and see that I’ve accidentally sent it with a mistake—“there” for “they’re”—I feel like a loser. OMG. She’s going to think I’m so dumb.

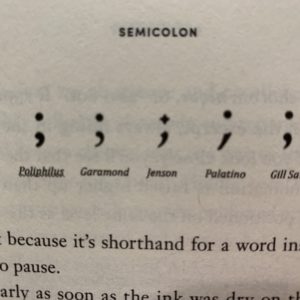

Through college and graduate school, I worked tirelessly to make sure I knew my grammar and spelling. I’d copy down beautiful sentences from famous authors or practice diagramming sentences out of my old Warriner’s Grammar book. What joy I felt when, at last, I understood the conjunctive adverb and how to punctuate it correctly: “I’m going to be stuck in that meeting for three hours; therefore, I’m going to make sure I have some crossword puzzles hidden in my bag.”

As I began to master (I’m using that word loosely here) grammar, I was proud, and, at times, I felt a bit smug when I detected the grammar mistakes of others. As a teacher, I’d bleed all over my students’ English papers with my favorite red pen, inserting the appropriate abbreviation, cs (comma splice) here or frag. (fragment) there.

Looking back, I wish I would have spent more time focused on what they were trying to say instead of the mistakes they made in saying it.

Cecille Watson, in her fascinating and inspiring new book, Semicolon, (I know what you’re thinking, but give it a try) says: “Rules can be a lazy way to put the onus on someone else. If you make a grammar mistake while trying to convey something heartfelt, I can just point out you’ve used a comma splice and I’m excused from confronting what you were saying, since you didn’t say it properly.” Please read those two sentences again.

What if we thought less about rules and more about communication?

Ironically, I was talking about this book and its message at a recent talk I was giving. Unfortunately, I used the old phrase “grammar Nazi” to indicate those self-styled grammar snobs and sticklers who look down on everyone else and delight in pointing out grammar errors.

It just kind of came out, even though I had actually told myself beforehand, “Don’t say, ‘Nazi.’” But in the moment, I couldn’t think of “grammar police,” a more neutral substitution, and “grammar Nazi” popped out. Someone in the audience took offense and sent me an email a couple of days later explaining why she had tuned me out after that.

First of all, I apologized. Words carry a whole lot of weight for people, and it was insensitive of me to use that word for humorous effect. I take great care to try to choose my words carefully and to take my audience into account whenever I’m speaking. Inclusive language is hugely important to me!

At the same time, if you speak as often as I do and are willing to put your ideas out there, you are no doubt going to make a gaff here or there or say some things that others don’t like.

But there’s a lesson here for both of us. While following rules can improve our skills and make us more sensitive to the impact of language on others, if we dismiss someone for making a mistake, even if the intent behind the mistake is not meant maliciously, then the whole point of sharing ideas breaks down and meaningful communication cannot take place.

As Watson points out, it’s worth thinking about the ethical costs of trying to build a fence based on a set of rules. First, it’s important to ask whose rules? And, second, it’s important to realize that the most primary value and purpose of language is true communication and openness to others.

By the way, if you find any grammar mistakes in this blog, would you mind keeping them to yourself!

Leave a Reply